To Borrow or Withdraw from a Banking Life Insurance Policy

This video explains why it may be more advantageous to borrow against your banking whole life insurance policy rather than take a withdrawal. It also explores the distinction between traditional debt and a collateralized policy loan.

Hi, this is Hutch with Bankingtruths.com and today we’re going to tackle the frequently asked question of, do I have to borrow from my own bank or can I just make a withdrawal? And I’ll tell you straight away that no, you don’t have to borrow from your own bank and yes, you can make a withdrawal.

However, there may be some clear advantages to utilizing the borrowing feature. And in order to demonstrate that we’re going to look at a mathematical example, but before we do that, we’re going to start with the concept on a sketchpad. So let’s first start by dissecting the concept of debt so that we can later differentiate it from the mechanics of the banking strategy.

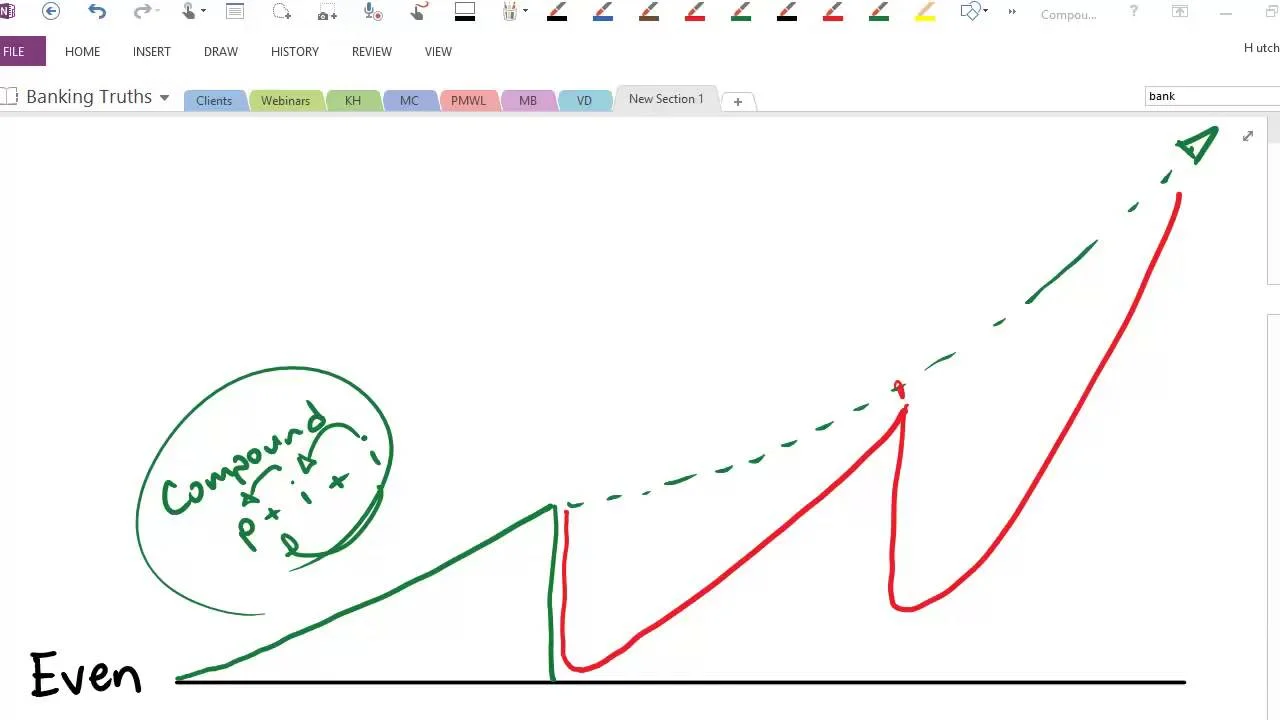

So if somebody even, and they have no savings and no debt in order to make a purchase, they’re going to need to use somebody else’s. We’re going to represent that here with the red line, bringing them below. Even now, this is debt. Interest is going to be accruing on this. And so in order to keep things from snowballing out of control and a Creek, keep their credit in good standing.

They’re going to make principal and interest payments to get themselves back to even, and by having that credit worthiness, if they want to make a later purchase later in life. They can again, use somebody else’s money, but again, they’re going to have to make regular principal and interest payments just to get back to even now the alternative to this is to save your own money so that you don’t have to use somebody else’s.

And so we have to start back here in time because you do have to spend some time and energy accruing your own money so that you can make that same purchase. And even though you don’t need to make that principal and interest payment to get back to even. You still need to make regular payments back to your savings account.

And I call this P minus interest because most of them are paying very good interest at all, on what interest they do pay starts with the dot, but you need to make these same payments to fill up your bank so that you can make the next purchase. And so the story goes, so what I want you to notice is that even though you’re on the right side of the line here, you’re really not making any progress with this block of funds.

Well, what’s the alternative you ask. And I think we’d both agree that the holy grail would be, if we could put our money in an account that would safely compound interest for us. And if you remember what compounding is, I call it it’s P plus I plus I, because not only do you earn interest on your principal, but after one year, it goes by you an interest on your principal.

And you were an interest on the interest that your principal’s already earned. So you get this wonderful snowballing steepening effect of this curve over time. Now I ask clients, would you rather have this side of the curve or this side of the curve? And everybody wants the far right. And there’s no magic bullet that gets you there.

It’s really just allowing that money to snowball like this over time. If we had this account and we could collaterally borrow against it at any time, for any reason, even if you did fill up the tank again, by paying off that loan you have against your compounding. There’s really no love lost. And in fact, you end up at a higher place in line so that you can do it again.

And if we compare this to our saver, even if we use the exact same cash flows, you can see the difference is staggering here. Now I know some of you are seeing these red lines and hearing the word borrow, and you’re literally seeing red. You’ve worked very hard to get out of debt or you’re in the process of working very hard to get out of debt.

And I commend you. But is it technically debt? If you have a corresponding asset that’s growing right alongside of it. So getting back to the original FAQ of, do I have to do all this borrowing stuff? Can I just withdraw my money? This account sounds great. And the answer is sure, but that defeats the purpose because as soon as you make the purchase and drain the account, you kill the compounding.

It’s gone. Right. It’s not happening anymore. It doesn’t matter how great the account is or what kind of interest you’re earning because you’re down here. And by the time you fill the account back up, you’re behind where this guy could have been by not interrupting the compounding in the first place. And the only way to do that is to have a feature in the contract that allows you to collaterally borrow against your compounding asset at any time, for any reason.

What I found is these semantics really caused stumbling blocks for even my most successful clients. And what I’m about to show you is a mathematical example that will hopefully demonstrate that if you can get past the mental notion that the word borrow automatically equals bad, that you’ll be able to put yourself in a better financial position overall by using this financial stress.

Okay. So what we’re looking at now is an actual policy designed for banking from a very reputable company. And I do want to disclose that these are non-guaranteed values. And so what is assuming is the company is going to continue to pay dividends every year, going through. With the current dividend scale.

And that could be good news because the current dividend scale is historically pretty low considering our low-interest-rate environment. And although there’s no guarantee, they’ll continue to pay a dividend. This particular company has paid a dividend every year since the mid 18 hundreds. That being.

What we’re actually looking at here is a 43-year-old. It says 44, but this is at the end of the year, a 43-year-old at the second-best rating, uh, taking out this policy and we’re going to fund premiums for only seven years. So you could pay for longer and you probably should pay for longer, but you don’t have to.

And in fact, if you wanted to get away with. You could probably do that too. And the minimum premium that’s due for this policy is less than $6,000. Uh, but if you want to fund the full 25 and you do want to, uh, overpay the minimum, so you can build up as much cash value as possible. The IRS requires us to have about 925,000 of death benefit.

So this is almost the minimum of death benefit that the IRS will let us have to fund this 25,000 a year for seven years. Now going forward after the premiums are done, you can see there’s a negative here. And this isn’t the total net outlay column. This means we’re taking out $140,000 policy loan. And then after that, we’re going to pay back seven.

$20,000 payments. So there’s 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and there should be another one here and there is actually, but we’re also taking out another one 40. So this last $20,000 payment is stepping on the $140,000 loan. And so the software nets it out automatically, and then we’re going to payback seven twenties, here’s five, and here’s two more.

So, this is essentially a mathematical representation of the green line building up this hundred and 75,000 a premium $25,000 a year for seven years. Uh, taking a policy loan of one 40 pain back just principal of the one 40 taking out one 40, again, paying back principle of the one 40 and having this full 1 75 compound the entire time.

Regardless of the policy loans for purchases. Now we’re going to compare this to, we have a separate calculator where we can plug in $175,000 into a cash account. Taking out one 40, putting the one 40 back, taking out one 40, putting the one 40 back and seeing what this ends up to in our benchmark. We’re going to use the year 23 numbers.

So age 66. And where to go. We’re going to look at the, uh, net cash value at the end of the year. In this case, it’d be 350,000. We’ll just go ahead and round down. And we’ll look at the net death benefit at the beginning of the year in this case, $877,000. So just write down those two figures, the three 50 and the 8 77, because we’re going to plug them into a different calculator.

All right. So this calculator is going to take the data that we ran. And over here, we’re going to plug in the policy input. So this is going to be our policy side, just like we saw it looked like this, and over here is going to be our cash side. And you guys are going to help fact-check my work. Uh, the annual payment we paid was $25,000 and we did that for seven years we made a purchase in year eight and we did it through a policy loan of $140,000.

We paid back $20,000 for seven years. And we did that twice. We’re going to notate that over here. And you’re 23, the policy cash value was just over $350,000. And the policy death benefit was a hundred, $877,000. Okay. So there’s a lot going on here and we’re going to play with some of these assumptions in real-time, but I want you to notice that I gave this a wonderful savings account, a 5% rate of return.

And, uh, and I said, our taxpayers are only paying 35% between state and federal taxes. I realize some of you may be paying more than some of you may be paying less. What this term cost is, is if you wanted that initial $925,000 of term to last for 20 years, it was actually more than a thousand dollars, uh, with the cheapest company out there.

But I just went ahead and rounded that down. And again, we did two cycles of this taking 140 out of the savings account and putting it back 20,000 at a time and a year 23. The term would have lapsed. So there’d be zero death benefit in spite of paying for the term and notice that how much cash you had, uh, would be just under $250,000.

This in contrast to the policy that even at today’s low-interest rates. Uh, it was $350,000 and there’s 877,000 of death benefit there that will endure it and it’ll grow or shrink depending on how you use the policy, but it doesn’t lapse after 20 years. So some of you may be saying, you know what, Hutch I’m in a state that doesn’t charge state tax, and I’m a fairly modest earner.

So I only pay 25% in tax and you know what? I don’t have any kids, so I don’t need to pay for term. Just notice that the cash account is still less than the cash value in the policy. And the reason just comes back to that, allowing this asset over here to compound, no matter what. Even in spite of the policy loans versus over here, you’re filling it up, taking money out, filling it up, taking money out, filling it up.

And if I press this button down here, we can go ahead and take a look at a spreadsheet depiction of that. And I think it’s really impactful to see exactly what’s going on. So, again, this is just the savings account we’re looking at. And if you put in $25,000 a year at 5% annual growth, you see you’re getting 1250 of, of growth.

And granted you have to pay some tax in this three 12 of tax, but let’s just focus on this column for a moment. As we fill up the account, notice what happens, our annual growth, how much we’re getting everything. Really gets up to some nice, critical mass up to about 10,000 of compounding in that seven-year.

And then what do we do in year eight? You pull out one 40 of it and what does it do to the compounding? It just crushes it. And even though you’re going to fill up the bucket back up in your compounding will go back up and you get up to that 10,000 again, what happens right here? You take out another one 40 and you just crush it.

So the reason why. Our strategy over to here as much more powerful as you are able to compound that full balance without crushing it. And let’s just go ahead and put a realistic rate of return here for a moment. Let’s just use something closer to what people are actually getting like one. And again, this is at the lower tax rate with no term we’re talking about an extra hundred and $50,000, 155 and change thousand dollars created out of thin air simply by repositioning your money and funneling your purchases in a more efficient way.

We can say, well, gosh, what happens? And I’m going to go ahead and put the other tax rate back and the term back, because a lot of my clients are higher-income earners and they do have responsibilities. Uh, what kind of rate of return we saw that five was behind. What about six were still behind? What about seven?

We’re still behind? What about 8%? We’re still behind. So even if interest rates go up on this side and for some reason they don’t go up over here. You’re still ahead, but if internet fixed interest rates did go up, you would probably see some increases in your policy. But for the sake of argument, let’s use a more realistic 23 year average of savings accounts rates.

And let’s just call it two and a half percent. Uh, over here you have 190, 2000 of cash leftover at the end of 23 years versus 350,000 of cash value. And this is with no increases over here. This is over 80% more cash value than cash, simply by repositioning your money. And I often ask clients, which one would you rather have?

Do you really want to continue to let banks and other financial companies reap the benefits from your savings throwing you pennies in between your purchases? Or do you want to learn how to harness the power of compounding continually with an account that’s contractually guaranteed to grow and knowing that you have contractual access at any time for any reason.

Not only that I know we downplay the death benefit, but just knowing that your savings account would basically double or more overnight in the form of a death benefit and come into your family’s life when they need it, the most that’s just something no other institution offers. It just doesn’t. At this point, I’d like to invite you to come to our website and take a look at the openings in our calendar book, call for yourself with one of our team members.

So you can take a look at your numbers specifically to make sure that this will be applicable to your situation. What I can tell you. And I think what you’ve seen here is for the vast majority of people, it’s an absolute no-brainer and hugely advantageous to their wealth-building efforts. We look forward to talking with you soon.

John “Hutch” Hutchinson, ChFC®, CLU®, AEP®, EA

Founder of BankingTruths.com